Research has primarily shown positive treatment outcomes when TGNC adults and adolescents receive TGNC-affirmative medical and psychological services (i.e., psychotherapy, hormones, surgery; Byne et al., 2012; R. Carroll, 1999; Cohen-Kettenis, Delemarre-van de Waal, & Gooren, 2008; Davis & Meier, 2014; De Cuypere et al., 2006; Gooren, Giltay, & Bunck, 2008; Kuhn et al., 2009), although sample sizes are frequently small with no population-based studies. In a meta-analysis of the hormone therapy treatment literature with TGNC adults and adolescents, researchers reported that 80% of participants receiving trans-affirmative care experienced an improved quality of life, decreased gender dysphoria, and a reduction in negative psychological symptoms (Murad et al., 2010).

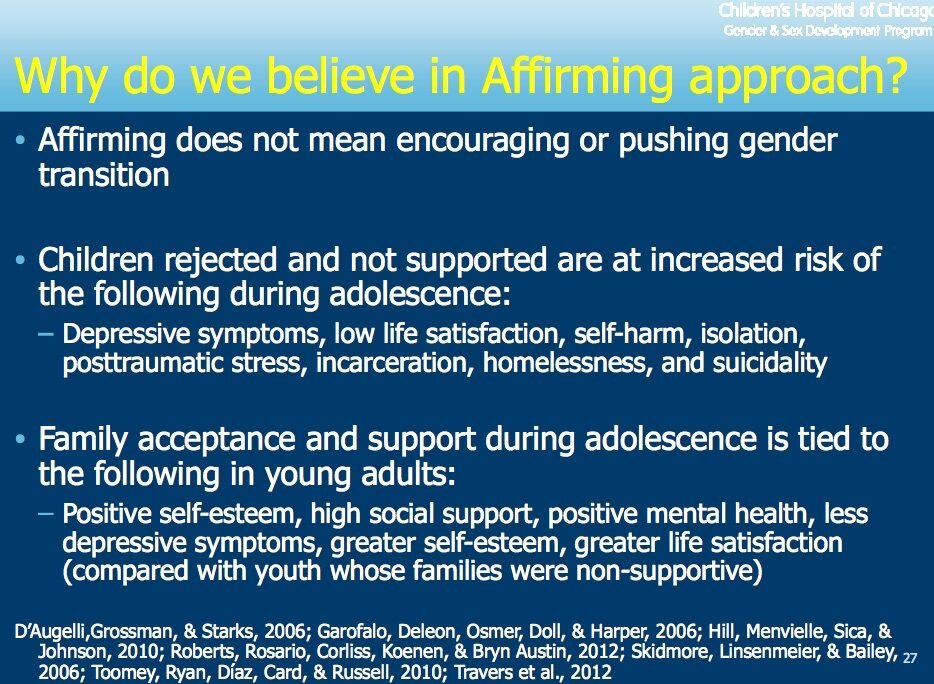

In addition, TGNC people who receive social support about their gender identity and gender expression have improved outcomes and quality of life (Brill & Pepper, 2008; Pinto, Melendez, & Spector, 2008).

Several studies indicate that family acceptance of TGNC adolescents and adults is associated with decreased rates of negative outcomes, such as depression, suicide, and HIV risk behaviors and infection (Bockting et al., 2013; Dhejne et al., 2011; Grant et al., 2011; Liu & Mustanski, 2012; Ryan, 2009).

Family support is also a strong protective factor for TGNC adults and adolescents (Bockting et al., 2013; Moody & Smith, 2013; Ryan et al., 2010).

TGNC people, however, frequently experience blatant or subtle antitrans prejudice, discrimination, and even violence within their families (Bradford et al., 2007). Such family rejection is associated with higher rates of HIV infection, suicide, incarceration, and homelessness for TGNC adults and adolescents (Grant et al., 2011; Liu & Mustanski, 2012). Family rejection and lower levels of social support are significantly correlated with depression (Clements-Nolle et al., 2006; Ryan, 2009).

Many TGNC people seek support through peer relationships, chosen families, and communities in which they may be more likely to experience acceptance (Gonzalez & McNulty, 2010; Nuttbrock et al., 2009).

Peer support from other TGNC people has been found to be a moderator between antitrans discrimination and mental health, with higher levels of peer support associated with better mental health (Bockting et al., 2013).

Bockting, W. O., Miner, M. H., Swinburne Romine, R. E., Hamilton, A., & Coleman, E. (2013). Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. American Journal of Public Health, 103, 943–951. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013 .301241

Brill, S., & Pepper, R. (2008). The transgender child: A handbook for families and professionals. San Francisco, CA: Cleis Press.

Byne, W., Bradley, S. J., Coleman, E., Eyler, A. E., Green, R., Menvielle, E. J., . . . American Psychiatric Association Task Force on Treatment of Gender Identity Disorder. (2012). Report of the American Psychiatric Association Task Force on Treatment of Gender Identity Disorder. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 759 –796. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/ s10508-012-9975-x

Carroll, R. (1999). Outcomes of treatment for gender dysphoria. Journal of Sex Education & Therapy, 24, 128 –136.

Clements-Nolle, K., Marx, R., & Katz, M. (2006). Attempted suicide among transgender persons: The influence of gender-based discrimination and victimization. Journal of Homosexuality, 51, 53– 69. http://dx .doi.org/10.1300/J082v51n03_04

Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Delemarre-van de Waal, H. A., & Gooren, L. J. G. (2008). The treatment of adolescent transsexuals: Changing insights. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5, 1892–1897. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j .1743-6109.2008.00870.x

Davis, S. A., & Meier, S. C. (2014). Effects of testosterone treatment and chest reconstruction surgery on mental health and sexuality in femaleto-male transgender people. International Journal of Sexual Health, 26, 113–128. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2013.833152

De Cuypere, G., Elaut, E., Heylens, G., Van Maele, G., Selvaggi, G., T’Sjoen, G.,... Monstrey, S. (2006). Long-term follow-up: Psychosocial outcomes of Belgian transsexuals after sex reassignment surgery. Sexologies, 15, 126 –133. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sexol.2006.04.002

Dhejne, C., Lichtenstein, P., Boman, M., Johansson, A. L. V., Långström, N., & Landén, M. (2011). Long-term follow-up of transsexual persons undergoing sex reassignment surgery: Cohort study in Sweden. PLoS ONE, 6(2), e16885. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0016885

Gooren, L. J., Giltay, E. J., Bunck, M. C. (2008). Long-term treatment of transsexuals with cross-sex hormones: Extensive personal experience. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental, 93, 19 –25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1210/jc.2007-1809

Grant, J. M., Mottet, L. A., Tanis, J., Harrison, J., Herman, J. L., & Kiesling, M. (2011). Injustice at every turn: A report of the national transgender discrimination survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality & National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Retrieved from http://endtransdiscrimination.org/PDFs/NTDS_Report .pdf

Kuhn, A., Brodmer, C., Stadlmayer, W., Kuhn, P., Mueller, M. D., & Birkhauser, M. (2009). Quality of life 15 years after sex reassignment surgery for transsexualism. Fertility and Sterility, 92, 1685–1689. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.126

Liu, R. T., & Mustanski, B. (2012). Suicidal ideation and self-harm in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42, 221–228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre .2011.10.023

Moody, C. L., & Smith, N. G. (2013). Suicide protective factors among trans adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 739 –752. http://dx.doi .org/10.1007/s10508-013-0099-8

Murad, M. H., Elamin, M. B., Garcia, M. Z., Mullan, R. J., Murad, A., Erwin, P. J., & Montori, V. M. (2010). Hormonal therapy and sex reassignment: A systemic review and meta-analysis of quality of life and psychosocial outcomes.Clinical Endocrinology, 72, 214 –231. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03625.x

Pinto, R. M., Melendez, R. M., & Spector, A. Y. (2008). Male-to-female transgender individuals building social support and capital from within a gender-focused network. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, 20, 203–220. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10538720802235179

Ryan, C. (2009). Supportive families, healthy children: Helping families with lesbian, gay, bisexual & transgender children. San Francisco, CA: Family Acceptance Project, Marian Wright Edelman Institute, SanFrancisco State University. Retrieved from http://familyproject.sfsu.edu/files/FAP_English%20Booklet_pst.pdf

Ryan, C., Russell, S. T., Huebner, D., Diaz, R., & Sanchez, J. (2010). Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescence and the Health of LGBT Young Adults, 23, 205–213.